As teachers, we don’t always have the time to go through everything that our students have produced – it’s also not always necessary. We want to get our students to the point where they can review their own work for strengths and weaknesses. So, how can we get there?

Three types of feedback

Feedback comes from one of the three Ps: professional, peer and personal. Professional feedback is from course tutors and anyone who could be considered the so-called expert. Students value this most because they feel that only the person who has been trained in this field has the knowledge and more crucially, the authority and expertise to review and comment on their work.

Peer feedback is difficult and often associated with negative feedback from fellow students. We need to encourage an atmosphere of collaborative learning and establish the goals of peer feedback. Just as professionals and experts have others review their work, our students can review each other’s work for strengths and weaknesses. When executed properly, peer feedback or assessment, can help students improve and recognise their own mistakes or weaknesses.

Reviewing one’s own work, giving personal feedback, is challenging for many students. Students are either too critical of their work or they see nothing wrong with what they have produced and are quite happy with their product.

Effective feedback

Giving effective feedback needs to be taught (and learnt). You cannot just have your students exchange essays and tell them to give their partner some feedback. They may not know what they should be looking for. Students may pick out unimportant aspects. They may also read the essay and summarise their feedback with a comment like, ‘That was nice.’ Or ‘I liked it’. Such statements don’t say very much about the work itself.

Here are some ideas on how to improve the quality of feedback from peer reviews and self-assessment.

Tip 1: Use rubrics to focus

Train students to give feedback and self-assess by providing guidelines on what to look out for. As with standardised exams, you can create rubrics which show students what they should be looking out for in a piece of work. Rubrics can be used for both spoken and written work and when designed well, should make the review process smoother. There are three types of rubrics.

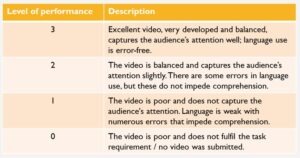

Holistic rubrics can help evaluate the overall quality of a piece of work and can be used with any type of work a student has produced. Use it to assess role plays, podcasts, and even shorter pieces of writing. It’s not difficult to design, and easy to use. As a starting point, decide on how many levels of performance you want. Then write the descriptors for the best and worst level of performance. After that, write the descriptors for the levels in between.

Here’s an example rubric used to assess 10-minute videos created by students.

If such a rubric is a little too general for you, or if you think your students need more guidance on what to look out for, why not try an analytic rubric?

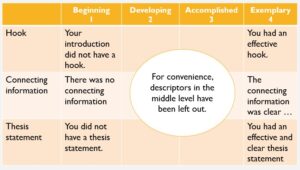

The advantage of this rubric is that it is strongly aligned to your learning objectives. The rubric focuses on different performance criteria and enables students to identify strengths and weaknesses in a piece of work. To create this type of rubric, decide what learning objectives should be demonstrated in the work, and then write your descriptors for the best and worst level of performance before writing the descriptors for the levels in between.

The following rubric assesses introductory paragraphs for an argumentative essay.

Another good rubric is one that focuses only on what students are expected to know and demonstrate in their work. Less time-consuming to create, you can use this rubric in self-assessment and also easily adopt it for peer review.

The following rubric was used to assess student podcasts. Three learning objectives were assessed here: the opening or introduction of the podcast, the content, and the delivery. The rubric identifies the minimum standard for each of these learning objects and reviewers would make their own observations in the columns on either side.

You can create your own rubric or use a ready-made one (just note that you might have to adapt the latter to suit your specific purpose). Here are some rubric banks for you to browse:

Tip 2: Personalize your feedback with the P-Q-P formula

Holistic and analytic rubrics don’t offer much room for personal comments. Use the P-Q-P formula with the rubric, or even on its own to encourage students to really think about what they’re reviewing. This formula works with both peer review and self-assessment.

P-Q-P stands for praise, question, and polish. Have students look at the piece of work and identify something that is worthy of praise, something that stands out or was done well. ‘Question’ requires the reviewer to pose a question (or more) about anything related to that piece of work. It could be content-related, language-related, or even process-related. In the last step, reviewers make suggestions on how the work can be improved., i.e. how to polish it up.

Tip 3: Feed forward and feed up

Have you ever noticed how feedback only looks back on a piece of work? Comments such as ‘You didn’t have a strong thesis statement’ or ‘The email had too many spelling errors’ tell our students what was wrong with their work. However, they do not necessarily tell them how to do better. While it can be argued that comments like the previous would imply that this is an area that needs work, the main message is still: ‘This is not good.’

Consider how you word your feedback and try to make your comments feed forward and feed up. When you feed forward, you’re telling your students what it takes to do better next time. Instead of ‘The email had too many spelling errors’, try ‘Check your work for spelling mistakes before submitting; there were quite a number of errors here.’

In feed up, make the link between what your students have produced, and why their real-world language needs to be clearer. With the example of the thesis statement, you could clarify your feedback as follows: ‘It’s important to know how to write a good, strong thesis statement because you’ll be doing a lot of that when you write term papers in graduate school.’

Conclusion

Feedback shouldn’t only come from you. While getting students to do peer-review and self-assessment may seem like something lazy teachers would do, the actual goal of this independence. Students need to be able to review their own work and those of their peers. When they leave your course, they won’t have you to give them feedback on their every move. And, move up and forward – feedback is important but so is feeding up and feeding forward!

***

If you find this article useful, you may also be interested in coaching principles for the ESL classroom.

Khanh-Duc Kuttig

Khanh-Duc holds an MA in TESOL and has been an ESL teacher since 1995. She currently teaches a range of language courses (always encouraging learner autonomy and creativity) at the University of Siegen. Besides, she's Events Coordinator for ELTA-Rhine and TESOL 'Teacher of the year 2021'.