Losing the Fear of Speaking English at Work: Helpful Mindset Shifts for Business English Users

For many non-native English speakers, concerns about their language skills lead to hesitation when speaking up in business meetings. In this article, Kath Robinson offers her insights and practical strategies for mindset shifts that help Business English users thrive.

In 2020, I found myself working with German clients for the first time. The English level of my average client here was higher than what I was used to in Spain, Japan, or Indonesia. However, despite the good level (B2 and above), clients were coming to me because they felt that they couldn’t/shouldn’t speak in meetings, or the worry about speaking and what everybody thought about their English was making them miserable.

The more I got to know my clients, the wider the gap between their actual and their perceived ability came to be. Why did Anna from HelloFresh chat with me happily throughout our 60-minute sessions on all sorts of topics with very few problems, but in her meetings avoided speaking if at all possible?

Why did Stephan from Netflix manage fine in his meetings with other non-native speakers of a similar level, but as soon as someone with near-native or native level was present, he felt his contribution wasn’t as valuable and barely spoke?

‘Confidence’, I hear you say!

While I believe confidence plays a part, over the last few years I’ve come to see ‘mindset’ as a more accurate description of the problem. Here, I’m not referring to a ‘growth mindset’ as coined by Carol Dweck (although there is some overlap). I simply mean, my clients have the wrong aim when using English at work:

They treat their English meetings like an English exam.

I often hear comments like:

- “I don’t speak because I might make a mistake.”

- “I sound so German.”

- “The words I use are so basic.”

This means they are putting all their focus on what others think of their English level, rather than the reason they are actually in the meeting, e.g. to share learnings from a certain project or plan the budget for the next quarter. This then has an extremely negative effect on how people are able to use the English they already have, as one or more of the following happens:

- People speak as little as possible, preferably not at all.

- People don’t listen to others because they are too busy planning what they

themselves are going to say. - People are so focussed on using long words and trying to sound professional,

their natural flow or ability to explain suffers. - People put so much pressure on themselves that they tense up, they come across as super underconfident or their mind goes completely blank.

How can you help a client develop a better mindset?

There are many, many things you can do depending on what the individual mindset hang-ups are: far too many to include in a short article!

However, here are four suggestions that are relevant in most cases:

- This article (with slight edits) is one I often share with clients as a first step:

Mindset Shifts that will Positively Impact Your English Fluency - I encourage my clients to take the time to work out exactly what it is that is worrying them about speaking English at work. I then ask them to write this down. Next to each issue, we come up with a more positive statement or a solution:

Issue: “I might make a grammar mistake.”

Positive statement: “Everyone knows that English isn’t my first language, so nobody expects my English to be perfect.”

Issue: “I might not understand a question.”

Solution: “If this happens, I will calmly ask them to repeat/slow down/rephrase as appropriate. If I don’t make it a big deal, nobody else will see it as a big deal.”

Issue: “The words I use are so basic.”

Positive statement: “The other people in the room are interested in my knowledge not how many long English words I use.” - Be selective with error correction. It’s very hard for someone to get over their fear of making mistakes if you are constantly pointing out their mistakes.

Personally, in most cases, I now only mention errors

-where understanding is affected

-that come up very often - Give clients plenty of speaking practice, particularly task-based activities and roleplays, and make the feedback more about task achievement than language.

This helps take the focus away from ‘this is all about my English level’ and puts it back on why they are in the meeting in the first place.

Say hello!

If you have any questions or would like to exchange ideas on this topic please do get in touch:

info@kath.robinson.english.com

Also, I’m currently looking for participants for the next season of my Just Talk Club. If you know any business professionals (from anywhere in the world!) with a B1 -B2 level, who find speaking English at work challenging or who are simply looking for a safe space to practice the English they need for work, the Just Talk Club could be just

what they need. I offer a 20€ referral ‘thank you’ if anyone you refer signs up.

Click the link below to find out more:

***

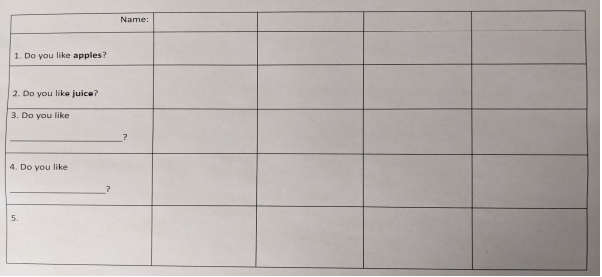

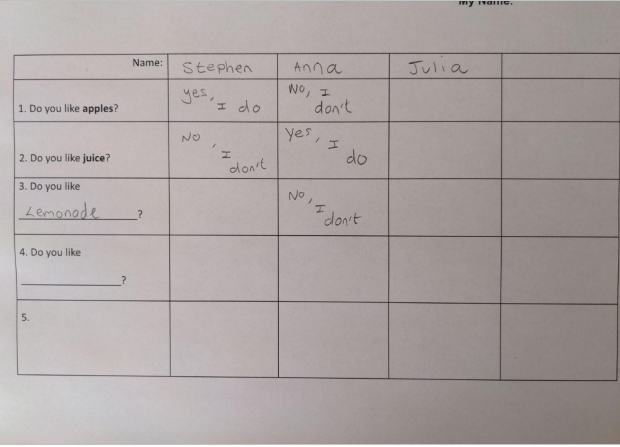

Here you can see an example, with the paper cut, so that each question is a removable strip.

Here you can see an example, with the paper cut, so that each question is a removable strip.