Gabriel EA Clark has a party trick: he can remember any 10 words you throw at him and then recite them back on command and out of order. This might not sound that impressive until you see it in action. And it’s even more fascinating when you learn how it’s done and how it applies to language learning.

In a comfortable room kindly provided by Cornelsen Berlin, 10 English teachers sat impressed on a recent Saturday as Gabriel explained the history of dual coding. From psychological studies in the 1970s came the idea that we remember new words more easily if we pair them with another word and corresponding image in our brains.

Memory hooks: words and images as mnemonics

The “keyword” mnemonic method grew out of these dual cognition studies and can help language learners create visual “memory hooks.”

For example, if I’m trying to remember the word “bruise” and I associate it with a picture of “Bruce” Willis with a black eye, I’m more likely to remember it (“bruise” sounds like “Bruce” and he gets a lot of bruises).

For second language learners, the process looks like a triangle. If an English speaker is trying to remember the Spanish word for “duck,” for instance, they might first consider that “pato” sounds a lot like “pot.” And if they then imagine a duck with a pot on its head, the resulting image is more likely to stick in their memory along with the associated words.

Baloney is better

Gabriel stressed that the weirder and more vivid the image, the easier it would be to remember. And he pointed out how the word-image association must be personal to the learner in order to work well. In most cases, giving a student your keyword association won’t resonate with them.

However, Gabriel expertly demonstrated how to teach the method to students so they can add it to their learning toolbox.

After practicing memorizing 10 random words using his party trick (the peg-word mnemonic device) and being pleasantly surprised how well we could reproduce the words, he then moved us into a pair activity learning unfamiliar Russian and Turkish words.

Pairs of teachers throughout the conference room were laughing out loud as we created absurd mental images and keywords: all to help us learn these new words.

And if vivid and weird work best, then we excelled!

Have fun with grammar – cheating allowed!

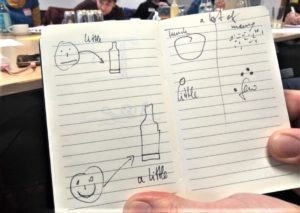

Even more laughter ensued in the next part of the workshop. Gabriel guided us in how to simplify drawings to quickly explain a new word or grammar point.

For example, we practiced how we might draw the difference between “a little” and “a few.” Not a few pairs drew a little wine left in a bottle next to a few grapes. Stick figures reading books were also very popular choices as we attempted to differentiate “bored” and “boring.”

The brain likes to cheat.

Gabriel emphasized that clarity and impact are key. He summarized the day’s practice by reminding us that “the brain likes to cheat.” Images are a favorite way it uses to hook new ideas and words into the fabric of its memory.

If we create clear, impactful images for our learners and also show them how to create their own vivid memory hooks, we can teach them to work with functions the memory already prefers to help them remember vocabulary.

Gabriel opened his talk by saying that the best learners aren’t necessarily the smartest, but those with the best strategies. I believe the same holds true for teachers. His workshop introduced us to some intriguing new strategies we can use with our students.

Check out Gabriel’s website to find out more about him and his book about learning with images.

For a very pictorial impression of the workshop, including a stunning “teachers’ art gallery”, please visit the HELTA blog.