Today has been a day of Cs – from the ‘Mini C’ of personal creativity to the ‘Big C’ of creative genius and beyond to a greater, shadowy C that had been lurking just out of sight but that today had its first tangible impact on our lives – the Corona Virus.

It was the day of the ELTABB AGM in the afternoon, following a morning workshop by Antonia Clare – writer, trainer and co-author of Total English and Speakout.

It was also this workshop that had been affected by the virus. Every introduction was punctuated by a peculiar half-dance, as participants wondered at the appropriateness of shaking hands. Having recently returned from a trip to northern Italy (to where the virus has spread), Antonia found herself in self-imposed quarantine in the UK, unable to join us in person.

Doubtless, there was much hair-pulling and screaming behind-the-scenes. But the ELTABB organisers and Antonia had arranged a video-conferencing solution. This was accomplished with calm panache and totally devoid of technical difficulties. (I will leave it to the reader to insert a computer-virus pun).

The solution provided us with our first lesson in creativity: It is not all about art and poetry – it is also about adapting to the unforeseen and being able to think on one’s feet.

Inspiration and the ‘internal syllabus’

Entitled “Be a Flamingo in a Flock of Pigeons” the aim of the workshop was to help English-language teachers understand the benefits of creativity. Not only for making lessons that are memorable but as a crucial aspect of language acquisition itself.

Starting with the maxim that ‘inspiration is everywhere’, we quickly grasped the advantges of allowing such inspiration into our lessons. Learners acquire language best when confronted with the unusual presented on a scaffolding of what they already know.

(This is something I can attest to. A number of my friends complained about Duolingo making them learn “Der Bär trägt seinen Hut”. In doing so they used the tricky masculine accusative possessive perfectly).

Each learner also has their own ‘internal syllabus’ – whatever they want to learn for their personal lives. When creativity is encouraged, they are able to tailor their learning to this syllabus, and lessons become more worthwhile.

Activity time: combining language with physical and visual elements

By enhancing her talk with numerous creative activities, Antonia showed herself to be quite the flamingo. She was able to keep a Saturday-morning audience engaged and ensured that the lessons we learned would be remembered for a long time to come.

For ‘stress statues’ we had to stand in lines, either crouched or upright depending on the stress patterns of particular words.

Language arising from the all-to-common “How was your week?” question (notorious for eliciting nothing but silence from shy teenagers) can be better produced by showing stock photos of hands or feet and asking questions such as “How does this person feel?”, “What have they done today?”, “Do they have any regrets?”

Such activities reminded us that stories are easier to remember than facts – a narrative will be clearer in a learner’s memory than a series of dry facts.

Involving emotions through such stories is just one reason to be creative; creativity also introduces higher-order thinking to the classroom. It helps students to use their language in a practical sense to create meaning and helps us as teachers stand out – to be the iconic flamingos.

However, there can be barriers to such creativity in the classroom: from a lack of time to environmental obstacles (such as a lack of equipment) or cultural mores.

The workshop finished with team brainstorming and sharing of methods to overcome such problems, and a reminder of how we can nurture creativity – such as by focussing our syllabuses on skills and capabilities rather than technical content.

Activities from the workshop – suitable for classroom use

All the activities come from the forthcoming book The Creative Teacher’s Compendium: An A-Z of creative activities for the language classroom by Antonia Clare and Alan Marsh (Pavilion ELT).

Stress statues

Groups of up to five people line up. They each represent a syllable in a word and must then crouch or stand up depending on whether their syllable is stressed or unstressed. Example: de-CI-sive = crouch, stand, crouch. This can help learners with phonetics, and also gets them moving, breaking up their desk-time and introducing variation to the lesson.

A favourite possession

Students each draw their favourite possession, then show their picture to others. The others must guess what the possession is and what makes it a treasure. This gets learners ‘thinking around’ a topic, starts conversations, and elicits more language than a simple description.

Hands and feet

A collection of photographs of hands and feet are shown on the board. The learners must consider a series of questions about this person, from the simple – “How old are they?”, “How was their day?” – to the more complex or personal – “What do they regret?”.

This uses language similar to that learners would use when talking about themselves. Students are more likely to feel comfortable talking about a ‘character’ than about themselves. As a consequence, more personal topics that might otherwise be unsuitable can be broached.

The game can continue with students having to introduce their chosen person to each other as though at a party. Their partner then has to guess which pair of hands and feet they are referring to. This places the language into conversation, giving the exercise a practical element.

Strangers on a train

Similar to the hands and feet activity, students must roleplay being strangers who meet on a train and start talking after one spills coffee over the other.

Again, this uses characters, allowing the students to feel more comfortable talking about topics that they may not normally want to talk about, or which they find more interesting (“I just got out of prison for killing somebody.” / “I work for NASA”).

If the teacher wishes to practise select vocabulary or encourage competition, then an alternative variant can be used – giving each student a card with a word or phrase that they must work into their conversation.

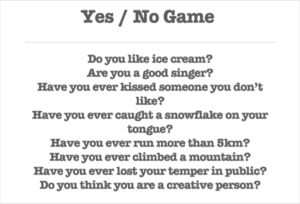

Yes or No game

Learners have to answer a series of questions without using the words ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Example questions included “Do you like ice cream?”, “Have you ever lost your temper in public?” and, of course, “Are you ready to start the game?”.

This is both surprisingly easy to do, and surprisingly easy to fail if you don’t pay attention. It also encourages students to use longer sentences and use a variety of affirmations and denials.

(The Irish language has no words for yes and no, and I once heard an Irish speaker responding to a series of questions in English. It felt frustratingly like they were playing this game very well!)

Five things in my kitchen

Each learner writes down five things that somebody would find in their kitchen. They must then choose one and think about how it is similar to themselves, explaining the reasons to their partner.

This turns a fairly dry vocab exercise into an imaginative (and tricky) story-telling game.

Have fun being the flamingo in a flock of pigeons! (Standing on one leg from time to time is highly recommended but entirely optional.)

The 3 Cs !!!

Nice. Thanks for the review Kit.

I really enjoyed reading your account of exactly what was covered that day and the circumstances of it all.

Bravo!

Brilliant! Thank you for the kind words!

Wow, fantastic review! And thanks for summarizing the activities. I was trying to write them all down for myself, but I was a bit occupied with the laptop 😉