Global societal and environmental issues were very much to the fore at the 2019 BESIG Annual Conference held in Berlin. It was a special and thought provoking event for many English teachers. Robert Nisbet took some time to reflect on some of the issues raised.

Back in September I was fortunate to receive an ELTABB scholarship which helped me attend the BESIG Annual Conference at Adlershof. One condition of this was that I write a review afterwards. What follows is my recap of the conference, plus some personal reflections.

The theme of ‘Back to Basics’ was addressed in a whole number of ways. Looking afresh at our day to day work as teachers and our relationships with our clients and learners, the conference considered broader questions about being human and our impact on the wider world. This included a focus on issues such as sustainability, the environment and inclusion.

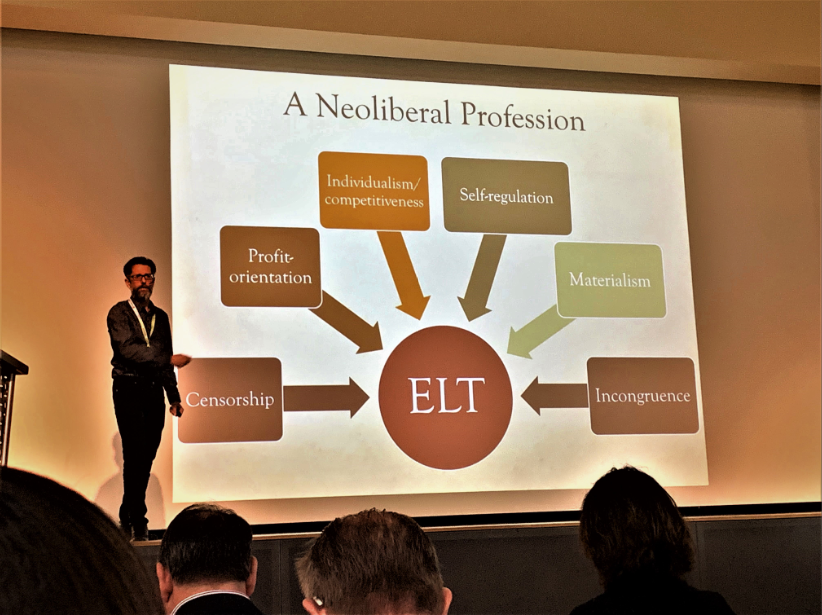

Here, I’d like to focus on the keynote talk given on the Saturday morning by Steve Brown from the University of the West of Scotland. It was entitled ‘Indoctrination, empowerment or emancipation? The role of ELT in global society’. Of all the talks I heard, this was the one which has kept resonating with me over the past few months.

Global responsibility in ELT: Some challenging questions

Steve’s talk began by reminding us of the many problems faced by people and societies in the world today, including climate change, inequality, racism and prejudice of all sorts.

Are we part of the problem or part of the solution?

Within this context he asked how we as Business English teachers stand in relation to these issues. Simply put, are we part of the problem or part of the solution?

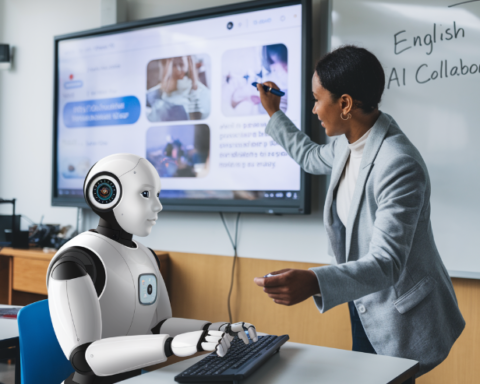

He asked us to consider in what way our teaching impacts the world, for good or bad. By teaching English within the context of business are we helping to promote a societal model which supports the prevailing culture of neo-liberal capitalism?

Through teaching English in order to help people communicate better and progress in their careers, we in turn help companies become more successful and profitable.

However are we merely adding to the troubles created by the dominant capitalist model of business and industry, which creates wealth and comfort for the few at the expense of the environment and of the health and happiness of the many?

Integrity in the classroom – emancipation vs. indoctrination

In response Steve offered an alternative vision of critical pedagogy in the tradition of Paulo Freire and Henry Giroux. He suggested that it’s our duty as teachers to always question and challenge prevailing cultural models.

…focus on the emancipation of our learners rather than on their indoctrination.

We should demonstrate alternatives, bring social justice issues into the classroom and focus on the emancipation of our learners rather than on their indoctrination.

Indoctrination in this case is often rather a subtle thing. It involves the promotion of a lifestyle oriented around economic success and the overall importance of international trade and business. This may include brief forays into content related to the environmental movement, cultural diversity and equal rights.

Steve’s view was that when we stop to look around and consider the scale of the issues threatening our world, such an approach is just not good enough.

He argued that at the moment, empowerment in ELT translates as ‘Learn English in order to be successful within existing structures’.

But this empowerment does little to challenge the deep and systematic inequalities in the world, and can be contrasted with a more emancipatory model summarized as ‘Learn English in order to participate actively in democratic society with a view to creating change’.

Facilitating change through critical pedagogy

Steve offered two useful definitions of the critical pedagogy he was promoting:

Critical Pedagogy…understands language learning as locally situated, personal, socio-historical, and political.

Jeyaraj and Harland (2016, p. 589)

as well as:

Critical Pedagogy…in ELT is an attitude to language teaching which relates the classroom context to the wider social context and aims at social transformation through education.

Akbari, ELT Journal, Vol. 62, Issue 3, 2008 (pages 276–283)

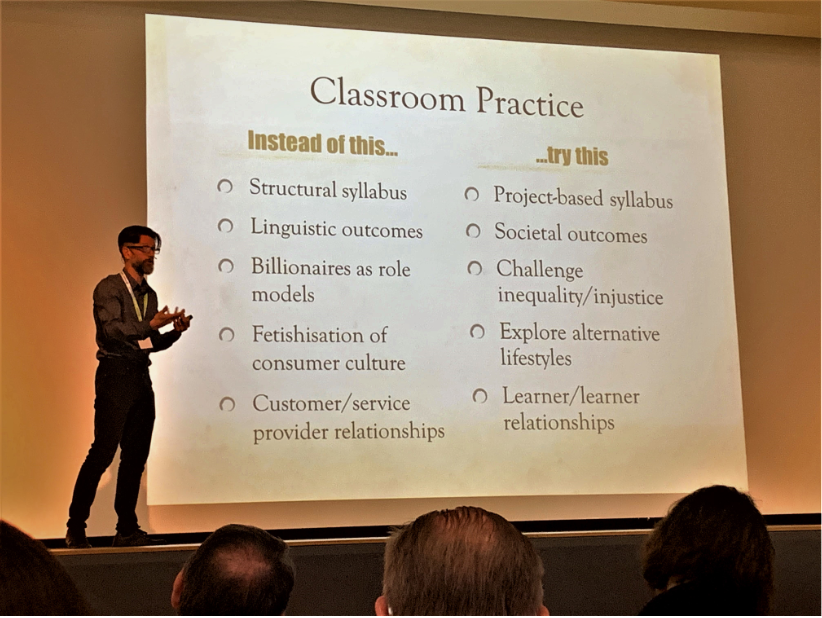

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the problems the world faces. If we as teachers accept the critical pedagogy model, that we can and should participate in trying to improve things, then there are a number of ways we can do this, as Steve suggested.

For one thing, these can include using social justice issues as the basis for the content of our lessons. Moreover, using participatory methodologies helps empower students in setting their own learning goals.

In such ways our lessons can be not just a means to develop language skills, but also a way to develop our students’ critical consciousness.

For those who work in-company, he argued that the next step could be to use English lessons to enable companies to look critically at themselves. Through creating internal reports and investigations within the lessons, he suggested that companies can assess how they can make progress towards:

- becoming more ethical

- reducing their environmental footprint and

- becoming actively and positively involved in local communities.

For those working with pre-experience learners it was also clear how lesson content could be re-orientated and space made for critical discussions.

Taking a personal stance

For me personally the talk resonated in many ways. I stopped being an architect and started being a teacher partly because I didn’t want to work for private property developers who I felt were benefitting the few at the expense of the many. I’m very sympathetic with the argument that we’re simply doing too little to address the problems of the world.

Amongst my clients are companies who build offices for global tech companies or who build trade fair stands for manufacturers of consumer products. I’d already asked myself in what way my teaching of their employees was having an impact on the waxing or waning of corporate power in the world.

Sometimes we do have conversations which are critical of aspects of the corporate world. Some of my clients are already working towards improving sustainability in their industry.

However the scope for critical pedagogy in my teaching is very much defined by external factors. That is, the culture of each particular company and the personalities, language-learning goals and interests of individual students.

That was my initial response to the challenging questions posed by Steve’s talk.

Critical pedagogy put into practice

I’ve had time to re-consider this response in the couple of months since the BESIG conference. It’s a question which hasn’t gone away, and which isn’t fully resolved.

In principle I’m completely in favour of bringing an agenda of social change to lessons. I’m sure I can do more in this direction. Some lessons have the scope to consciously look at more varied material, some don’t.

Still, I think it’s also important to recognise how people react to lesson content. My ongoing challenge with many of my lessons is to find content that my students find interesting.

When I’m successful, a topic, a video, some images or a text can spark an engaged conversation which is stimulating in itself; and this is also a good vehicle for improving their language skills. If students are not interested or engaged then language learning is very difficult.

Given the right conditions, the lesson can be an arena in which something can emerge.

I rarely know how the students are going to react to the lesson; and that’s one of the most wonderful things about being a teacher. Indeed, what one group finds very engaging, another may find deeply boring. Yet, this is impossible to predict. Given the right conditions, the lesson can be an arena in which something can emerge.

Final thoughts

I’m comfortable with telling my students what’s right and wrong with respect to the English language. I’m also happy to discuss ethical and controversial issues, and give my own opinion. But I would feel uncomfortable trying to deliver a more didactic ethical message. I generally want to let people make their own minds up, come to their own conclusions.

I accept that other more didactic approaches are possible and may be successful with different groups of students. Over the following months I will continue to question my approach in the light of Steve’s talk.

References

Joanna Joseph Jeyaraj and Tony Harland – ‘Teaching with critical pedagogy in ELT: the problems of indoctrination and risk’. In ‘Pedagogy, Culture and Society’, Routledge, 2016, p.589.

Ramin Akbari – ‘Transforming lives: introducing critical pedagogy into ELT classrooms’. In ‘ELT Journal’, Volume 62, Issue 3, July 2008, Pages 276–283.