What is neurodiversity and how does it affect language learning? How can we identify learners who may have specific learning differences and what should we do then? And perhaps most importantly: How do we deal with differences in a neurodiverse classroom?

Neurodiversity is a convenient term for the whole range of cognitive differences that we might find in our classroom. As a species, we humans are neurodiverse. That is, we all have slightly different cognitive profiles, so that some of us find some things more difficult than others do.

There are some individuals who seem noticeably different from their peers, and these people may have a specific learning difference (SpLD), such as dyslexia or dyspraxia. SpLDs are best thought of as different ways of perceiving the world, processing information and interpreting sensory input. They are not illnesses, or disorders – just differences.

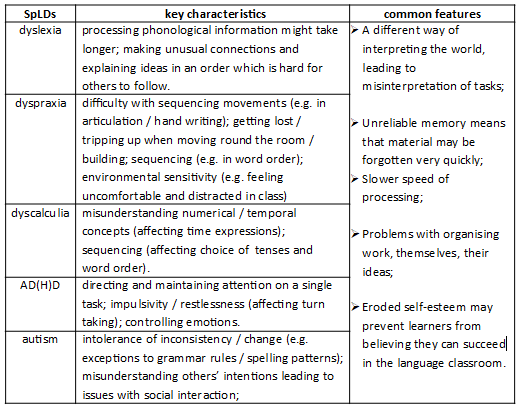

The most commonly identified SpLDs are:

- dyslexia

- dyspraxia

- dyscalculia

- AD(H)D

- autism

They affect language learning in different ways, but there is a lot of overlap and common ground between them, too. Here is a list of key characteristics and common features of these SpLDs:

How can we identify learners with specific learning differences and what should we do then?

If we notice that a learner is displaying some of the characteristics laid out in the table above, it might be a clue that we might need to keep a closer eye on them, and perhaps start to do some further exploration to identify their barriers to learning.

Observation is the key to recognising which learners may be experiencing difficulties. It’s something that all teachers do – even subconsciously – so that we can manage the classroom: knowing who is likely to start tasks first, who will want to ask a lot of questions before they begin, who will finish first, and who will be easily distracted.

It is helpful to make a note of any unexpected behaviours that we notice so that we can see if they are just a one-off or if they are patterns that may indicate a long-term issue. We can ask other members of staff to share their perspectives and see if the same issues arise in other contexts, outside of our classroom.

If, after a short period of observation, an SpLD is suspected, an informal conversation with the student would be helpful to find out how they see the situation and reassure them that we are going to do whatever we can to support them.

We could ask about their home life, how they are enjoying their English course (and other subjects) and whether they or anybody else in their family has ever experienced these kinds of difficulties before. This may be a way to open the conversation about possible screening, or further assessment.

Doing some detective work

In order to determine if it is an SpLD or just a temporary situation brought about by physical or mental ill health (e.g. stress, anxiety) there are certain things we need to consider. We should try to find out as much as possible about:

- the student’s background

- their literacy development

- their memory

- their speed of processing

- their phonological processing

We can start to gather information about the student and their background through observation and conversation. A questionnaire, where they answer questions about previous educational and life experiences, could help make this more concrete. This could cover elements of cognitive function such as memory, speed of processing and phonological processing, which might tie in with the information gathered through observation in the classroom setting.

There may be a person in your school or college who is responsible for supporting learners with SpLDs, and it would be helpful to work with them to decide the best way forward. Using the screening tool ‘Cognitive Assessments for Multilingual Learners’ (available from the ELT well website) can be a useful means of gathering all of this information, and also of making sense of what the data is indicating.

Formal assessment is not always necessary if the teacher is able to adapt to the learners’ different ways of working.

How do we deal with differences in a neurodiverse classroom?

This is the question that many teachers find most challenging, as there are so many ways that learners can be different. As noted at the beginning of this article, we are a neurodiverse species!

The key is to try to implement inclusive teaching practices in as many ways as possible, thinking about the learning environment, the materials you are using and the tasks you set, and most importantly, the relationships that are encouraged in the class.

Classroom environment

Remembering that some learners may be very sensitive to the physical environment, it is good practice to check that everyone is happy with the temperature in the room, as well as the lighting, noise levels, the equipment available and the layout of the furniture.

There may not be much that teachers can do about some of these things, but at least indicating that you are aware of these barriers can make learners feel more included, and cope better with some discomfort. Bringing their issues to the attention of the school management may result in changes that would benefit everybody.

Materials and tasks

Not all teachers are able to choose which materials are used on a course, but where possible, it is helpful to choose handouts or books that have a very clear layout. Images over text make it hard to read, and too much information on a page can be daunting. If the characters broadly represent the members of the group, that can be very motivating.

But the key with any materials is the way in which they are used.

Teachers may want to supplement coursebooks with additional resources or pick out key activities to focus on. Ideally, learners would be led through a section of new material in small steps, securing each bit with lots of recapping and revising before moving on. Incorporating multisensory activities that engage multiple senses at once is useful for this.

Explicit instructions and feedback are crucial, and getting learners to reflect on their learning is a valuable tool in developing self-awareness of their own learning processes.

Relationships

Good relationships between the teacher and the students, as well as between the students, are fundamental to any inclusive classroom. Creating opportunities for everyone to get to know and understand each other (and themselves) leads to greater levels of respect, acceptance and a sense of group belonging. It allows teachers to make better choices when putting students into pairs or groups so that students can bring out the best in each other.

It is the teacher’s job to create a nurturing environment for all learners, and to model the kind of supportive behaviours that we would want the whole class to adopt. This could mean looking for the positives and drawing attention to them (“Great idea!” “You really listened to your partner in that activity”,“I’m really pleased you came in time for the start of today’s lesson”) so that learners who are normally on the back foot (or always in trouble) can feel good about themselves, and about learning.

Stay positive, and have faith in your learners’ abilities to find their own strategies to cope with your class. Most importantly, show that you believe in them so that they can believe in themselves.

***

Suggested resources

Evens, M. & Smith, A.M. (2019) Language Learning and Musical Activities Morecambe: ELT well [available from www.matthewevensmusic.com or www.ELTwell.com]

Kormos, J. and Smith, A.M. (2012) Teaching Languages to Students with Specific Learning Differences. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Smith, A.M (2015) Cognitive Assessments for Multilingual Learners. Lancaster: ELT well. [Available from www.ELTwell.com]

Smith, A.M. (2017) Including Dyslexic Language Learners. Lancaster: ELT well [available from www.ELTwell.com]

Smith, A.M. (Ed.) (2020) Activities for Inclusive Language Teaching: valuing diversity in the ELT classroom. London; Delta Publishing

Anne Margaret Smith

Dr. Anne Margaret Smith started her career as an EFL teacher around 30 years ago. Alongside her language teaching, she also works as a dyslexia assessor and specialist tutor and is currently also training to be a Speech and Language Therapist. She founded ELT well in 2005 and offers professional development and resources to language teachers in all contexts.