The idea of task-based learning (TBL) is to create a ‘realistic’ learning environment in order to help language students prepare for real-life situations. While this in itself motivates learners to speak, studies suggest that immediate repetition of ‘real-world’ tasks may have further beneficial effects.

TBL: learning through meaning

Since its rise in popularity, task-based learning has become prominent in recent language teaching pedagogy. Unlike form-focused approaches, TBL places the communicative focus on meaning. Through language production, learners may notice ‘gaps’ between what they want to say and what is produced.

By detecting those disparities, students learn to give attention to the repair and replacement of the language for improvement on subsequent occasions.

The effect of this shows in language complexity, accuracy, and fluency (CAF).

Why speaking matters

Swain (1995) states that:

The activity of producing the target language may prompt second language learners to consciously recognize some of their linguistic problems.

(p. 126)

As Swain suggests, without output, speakers are unable to ‘practise’ the language and, in turn, notice discrepancies within their interlanguage system.

Furthermore, when gaps between what is said and what a learner wants to say are noticed, psycholinguistic processes are likely to be prompted to merge that newly acquired knowledge into the speaker’s interlanguage system.

This means that students who self-monitor their progress through speaking should improve automatically with practice.

But before we move on, what actually makes a valuable speaking ‘task’ in TBL?

Different types of ‘tasks’

Skehan (1998, p. 95) combines several definitions and takes the most prominent features to create an overarching definition:

“a task is an activity in which:

- meaning is primary

- there is some sort of communication problem to solve

- there is some sort of relationship to comparable real-world activities

- task completion has some priority

- the assessment of the task is in terms of outcome.”

Besides that, there is another type of ‘task’ claiming to replicate the meaning-oriented language of everyday situations. These tasks are called ‘pedagogical’ tasks.

Ellis (2003, p. 347) describes them as “designed to elicit communicative language use in the classroom, e.g. Spot-the-difference. They do not bear any resemblance to real-world tasks although they are intended to lead to patterns of language use similar to those found in the real world.”

Despite the meaningfulness of communication present in pedagogical tasks, the language that arises through them cannot be directly compared to the language a learner needs to complete tasks in the real world, as these are semantically and pragmatically different in nature.

TBL and repetition in language learning

So far, it is apparent that through interaction in meaning-focused, communicative tasks, learners engage in cognitive processes which seem to help monitor their language (Levelt, 1989, p. 460). Also, they help them notice language discrepancies in their interlanguage (Swain, 1995, p. 126).

Moreover, it seems that, through the repetition of a task, the cognitive work through prior conceptual processing is more accessible on subsequent occasions. This, in turn, most likely promotes language production and deeper acquisition.

If these assumptions are valid, repeated TBL could prove to be a useful tool to facilitate language learning. So how about some academic research to explore the effects of TBL and repetition on CAF (complexity / accuracy / fluency)?

The research methodology

In my study, I examined five non-native speaker (NNS) students enrolled in an English Language Teaching (ELT) programme. Each participant was to attempt one oral, monological task twice, with a ten-minute break between the two tasks. The task was identical on both occasions.

The task question was: “Can you tell me about your last holiday? Where you went, what you did, how you travelled there, and how you felt on the holiday.”

Results

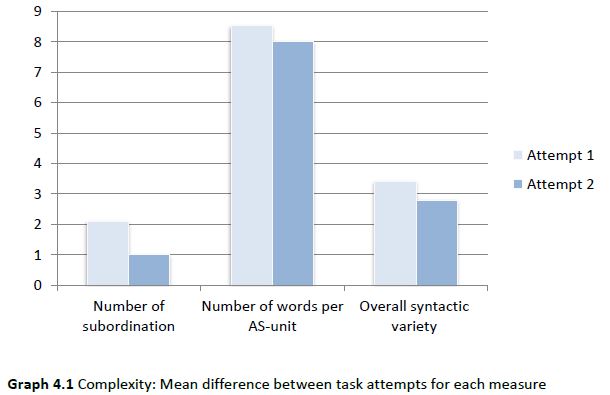

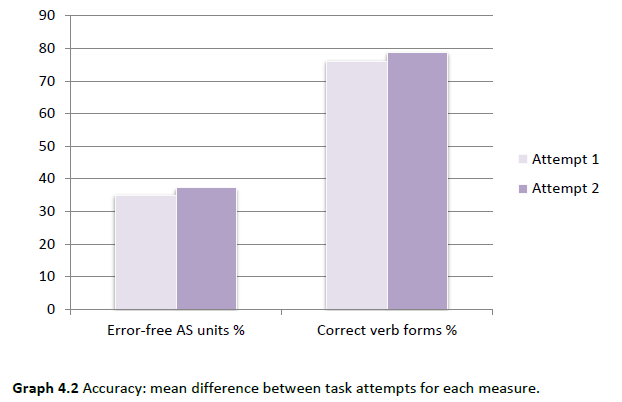

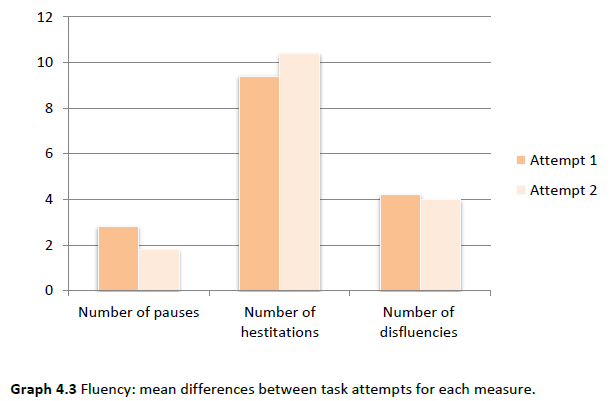

This section provides a series of bar charts that analyse the mean difference between the first and second task attempt and for each measure within each CAF construct.

In order to designate speakers’ individual utterances, the term AS-unit is used (analysis of speech-unit).

Complexity

Accuracy

Fluency

Self-evaluation

The results showed a marginal increase in accuracy and two measures of fluency, but these were found to be statistically insignificant when scrutinized again later.

However, the analysis does report an overall increase in accuracy and an overall decrease in complexity. This may support the validity of the data found in this study as it conforms to the notion of the trade-off effect between CAF constructs.

In contrast with the inferential data, the learners’ perception of task repetition turned out to be positive, insofar as gains in all CAF constructs and overall performance were reported.

This supports the idea that task repetition has a considerable effect on learners, although this study did not investigate into how or why this occurs.

Pedagogical implications and conclusion

Despite the data not showing significant differences between the attempts, improvements were recorded in the self-evaluation feedback. This could be because repeating a real-world task in the classroom, as opposed to a pedagogical task, may seem more worthwhile to students in terms of using time more effectively in class.

More importantly, the subjective increase in ability to complete a linguistic task in a second language could well lead to an increase in motivation and thus better learning of the target language.

As a conclusion, repeated TBL can indeed help promote learner motivation and confidence and make learners better students of a language, even if the objective data related to their performance do not support the subjective improvements immediately.

References

- Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Massachusetts: MIT

- Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Swain, M. (1995). Three functions of output in second language learning. In G. Cook, & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Principle and practice in applied linguistics (pp. 125-145). Oxford: Oxford University Press.