From Surviving to Thriving: Nurturing Teacher Wellbeing in ELT

We’re better able to excel as teachers when we take care of our own wellbeing first. But what exactly is it, and what small steps can we take to better support it? Christine Muir highlights simple ways to nurture teacher wellbeing for greater balance and fulfillment at work.

From anger to action

Think back to the height of the pandemic in 2020. It might be an unexpected initial prompt for an article on teacher wellbeing, but it’s the start of my story. A phrase that’s stuck with me since is the following: while we all found ourselves in the same storm, we were all in very different boats.

For some, experiences of lockdowns, social distancing, professional and social moves online, furloughs from work – all offered some net positives for wellbeing. For many others, the opposite was true. Certainly, this was sadly the case for many teachers.

There had already been a growing focus on ELT teacher wellbeing for many years before the pandemic. For me, though, it was the pandemic that catalysed my professional relationship with it. My frustrations grew to anger, which ultimately tipped over into action. Whose responsibility was it to protect teachers’ wellbeing?

Furthermore, what actually is wellbeing? How could I better support my colleagues and students? Was there also agency to support my own wellbeing that I was leaving on the table?

What exactly is wellbeing?

As a field of study, positive psychology is interested in understanding how we thrive.

Interest in wellbeing and what it means to live well extends back far beyond the modern concept’s inception – think, for example, back to philosophers Aristotle and Epicurus in Ancient Greece.

Historically, there have been two main approaches to understanding wellbeing:

1) Hedonic wellbeing focuses on our experiences of happiness and pleasure. For example, we might experience hedonic wellbeing during a fun lesson with a student or when enjoying a networking event with peers.

2) Eudaimonic wellbeing taps into something deeper. We experience it for example when we feel like we’re growing as a teacher or leader, developing our skills or finding new purpose in our work.

Wellbeing is multidimensional. Both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing are important.

Stop and think: When did you last experience hedonic and/or eudaimonic wellbeing at work?

What were you doing?

Did it feel like a rare/common experience?

How did it affect the rest of your lesson/the rest of your day?

Martin Seligman’s PERMA model of wellbeing

Martin Seligman’s PERMA model of wellbeing had the most meaningful initial impact on me in terms of increasing my own wellbeing literacy. That is, to answer the question of how I can better understand, assess and ultimately support my professional wellbeing.

It combines both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects:

P = positive emotions – joy, gratitude, hope, pride…

E = engagement – when we can get fully ‘stuck into’ challenging tasks, drawing on all our skills, strengths and attention

R = relationships – with other teachers, students, and outside of work

M = meaning – serving something bigger than ourselves

A = accomplishment – feeling competent and recognised for it

V = vitality (or PERMA+) – a later addition, our physical wellbeing is part of the same picture!

Read more about Martin Seligman and the work of the Positive Psychology Centre on their website.

Stop and think: Conduct a wellbeing health check-up

• What aspects of your wellbeing have been highest this week? Where has it been lowest?

• When has your wellbeing felt most stable over the past [month, year]?

• Where does your wellbeing currently feel most vulnerable?

• Choose one aspect of your wellbeing you want to focus on increasing over the coming week, month or year.

Do we have to wait for change?

There’s a short answer to this question: no!

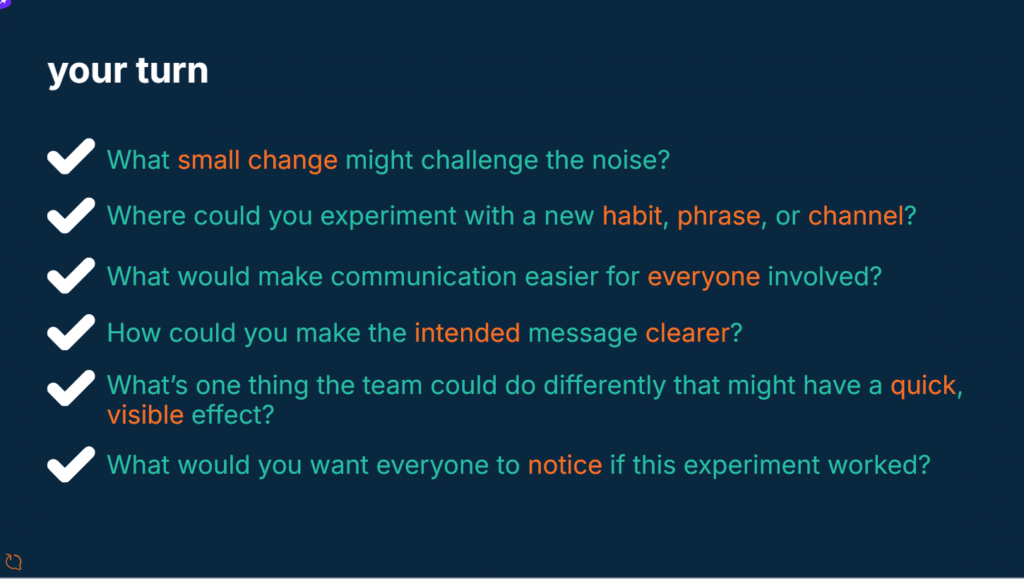

Let’s not pretend that all challenges are within our control, nor that all those that are have quick fixes. But this doesn’t mean that we have zero agency.

Stop and think: What does your job cost you? What challenges are you currently facing? What resources do you have access to?

One way to increase the amount of agency we feel we have – and so the amount we’re able to enact – is by personalising a job demands-resources model. It’s exactly what it says on the tin. It pushes us to better articulate the demands of our professional role and the resources we can draw on.

1) Start by noting down all the demands that come with your job. Big or small, in/outside of your control, jot down everything that causes you stress.

2) Separate out your list into two columns, stressors that you have some power to influence, and those entirely outside of your control.

3) Where stressors are inside your control, consider what small, tangible changes may be possible.

4) List all potential job resources available to you. These are things that safeguard us against the demands of our job. They can be things that you’re already doing or things you’ve not tried, networks you’ve not yet tapped into.

5) Finally, think bigger picture and consider opportunities to expand your learning and professional development.

Find this activity (p. 21), and others like it, in Sarah Mercer and Tammy Gregersen’s book “Teacher Wellbeing”.

Consider also tagging on an extra step at the end. Use your reflections as an excuse to catch up with a friend over coffee – consider sharing your list of resources and asking them to add ideas you might have missed.

Even if you come away ‘only’ having had a lovely catch up and spoken nothing about work, from a wellbeing perspective, the time may nevertheless have been well spent!

Ringfencing time in busy professional (and personal) lives isn’t easy. But, as workshop participants fed back, these ‘deep conversations’ around ‘thought-provoking questions on wellbeing in our profession’ are invaluable: ‘These questions are at the heart of our working lives.’

Ask not only what you can do for your teachers’ association, but also what it can do for you

Another lasting impact of the pandemic has been increased visibility, acceptance and (in many contexts) respect for discourses around wellbeing. Earlier this year, I was honoured to be invited to give a keynote talk on teacher wellbeing at the 33rd AKS conference held at Ruhr Universität Bochum. My ELTABB workshop invitation was prompted by a suggestion from someone I met at this conference.

This raises an important question:

➡️ Whose responsibility is it to support our wellbeing? Is it ours? Our employers’? What important roles can teachers’ associations like ELTABB play? Where is the balance?

There’s no single answer. But I do know that increasing our wellbeing literacy – our understanding of what wellbeing actually is and how we can better support it – matters. It’s a critical starting point for us to be able to make meaningful positive change.

Return to your wellbeing health check up periodically and take note of the direction it’s trending. Take advantage of the CPD available. Attend the next Stammtisch.

ELTABB, alongside other teachers’ associations, play a vital role in bringing teachers together and in facilitating these conversations.

Thank you, again, for the invitation and the opportunity to participate in such thought-provoking discussion!

***

If you enjoyed this article, you might also be interested in:

and

What I Wish I’d Known: 6 Tips for New English Teachers – Connections