Wow Your Audience without Words: Top Tips from a Public Speaking Expert

Some time ago, I had the pleasure of attending Friederike Galland’s “Speechless Rhetoric” workshop. What sounded a bit counterintuitive at first, turned out to be a day full of wow moments, personal growth and insights into public speaking. Here are my key takeaways for becoming a better speaker.

After welcoming us into her home and feeding us fresh cinnamon buns with strawberries and cream, Friederike kicked off the day by lifting the secret behind offering speaking workshops – without actually focusing on speaking.

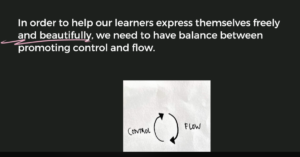

She explained that, due to our cognitive evolution, our brains are hardwired to focus more on visual cues than auditory input.

Therefore, body language plays a key role when giving a speech:

If it feels “off”, it can undermine the speaker’s message, no matter how interesting the content is, whereas effective body language and a punchy delivery can captivate an audience – even if the presenter is trying to sell sand in the Sahara.

Overcoming content

With the above in mind, we started practising speaking. There was no speechwriting, and there were no scripts involved.

Instead, the whole day was filled with little partner exercises, improvised speeches and feedback rounds. Each exercise was followed by each participant briefly speaking about their experience in front of the group, so we all had something to talk about. (For example, one exercise involved looking into another person’s eyes for two minutes). The feedback then consisted of observations about the delivery and tips for the next round.

By the end of the day, everyone had made half a dozen little “speeches” – without worrying about content at all.

Speaking tips

Here are the speaking tips Friederike gave us during the workshop. All of them are “non-verbal” tweaks to support effective speech delivery.

1. The Queen doesn’t hurry

The first tip was simple:

Take your time as you make your way to the stage.

It can be challenging to feel other people’s gaze on you, but this is your moment and you are setting the tone. If you’re nervous, your audience will pick up on that and reflect your nervousness. If you want to create rapport and grab your listeners’ attention, take your time, catch your breath and relax. Friederike told us to remember that “the queen doesn’t hurry”. And as the Queen or King of your speech, you have all the time in the world.

We practiced this a number of times. Whenever someone made a “rushed entry”, Friederike would ask them to sit down and try again, with the conscious choice not to hurry. It quickly felt natural after a few rounds.

2. …and she’s carrying shopping bags

After practising the entrance, we discussed an issue that a lot of speakers face – the right posture. This is more of a beginner’s problem, so with time and experience, you’ll feel more comfortable in your skin.

For practical purposes, the tip Friederike gave us was to “imagine carrying shopping bags”. That way, if you stand in front of your audience, your arms and posture will naturally fall into place. Once you start speaking, you will (also naturally) start gesturing, which is fine. Thus, think of the “shopping bag posture” as the baseline from which to proceed, and come back to it whenever your hands aren’t busy.

3. Tap into the power of the pause

Once you’re standing in front of the audience, it’s tempting to start speaking right away to avoid that dreaded awkward silence. However, Friederike suggested the opposite: to lean into the silence and use it to your advantage.

If you start with a pause, you will create tension and grab your audience’s attention. They will sense that the silence is the lead-up to something meaningful. As a consequence, whatever you say will carry more weight and people are more likely to listen closely.

Thus, it’s best to take a moment before you start talking. Have a look around and get a feel for the audience and the room. If you can, briefly look at every individual person and acknowledge their presence. Then, begin your speech.

4. Speak to one person at a time

We then went on to discuss how to speak to engage the audience. Friederike’s top tip here was to break down your speech into small chunks and make rotational eye contact while speaking.

So when you start, pick a person from the audience and make eye contact with them. Say your first phrase or chunk of lines. Speak to them directly, and only them. After that, focus on a different person while you deliver your next phrase. Keep repeating this for the rest of your talk. Only speak to one single person at any given time.

If you keep making eye contact throughout your speech, you’ll create a sense of privacy and immediacy. And interestingly, everyone will feel addressed, whether or not you have directly spoken to them. As a result, your audience will feel more engaged and interested in your speech.

5. Find your cheerleaders

This tip ties in with the previous one. When you give a speech, your audience will be diverse: not everyone will be equally attentive and eager to listen. So if you sense a lack of interest in some corners, look out for people who are engaged and supportive. They will be the ones to nod in agreement, laugh at your jokes and generally give you signs of acknowledgement.

These are people you can reconnect with to make personal eye contact, and they can help you through rough patches if your speech doesn’t quite go as planned. Plus, you’ll feel more confident and supported.

Bonus tip: Accept the applause

Once you’re done speaking, you may be tempted to leave immediately and breathe a sigh of relief because it’s finally over. While understandable, that’s not the best way to end a speech. Here’s why: you have established a connection with your audience. They’ve enjoyed interacting with you, and they want to show you their appreciation. If you run off immediately, it will feel like you’re cutting them short.

So Friederike’s advice was to see the applause as part of the speech and to allow yourself to receive it. After all, you’ve delivered a great speech, so give the audience a chance to celebrate you! Also, it will feel more natural and calming to embrace the applause, as it will give you non-verbal feedback and closure.

Enjoy becoming the best speaker that you can be, and don’t forget your shopping bags!

***

If you’d like to put the tips from this article into practice, one of the best ways to do so is to join a Toastmasters group in your area. You can find your local club on the Toastmasters website: https://www.toastmasters.org.

You can find out more about Friederike Galland and her work on her website and LinkedIn profile.

***

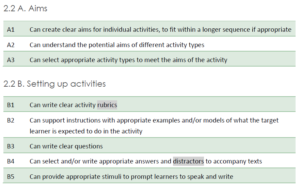

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in this post with presentation tips for English trainers.