Learner Autonomy and Teacher Wellbeing: Flip Your Classroom and Achieve More by Doing Less

This article explores the journey a teacher may embark on to support learner autonomy. It also looks at the challenges and benefits this entails for both the teacher and the learner.

In an earlier article for ELTABB, we focused on how language coaching can support students in a way that provides empowerment and true motivation.

This time, we’re taking a look at the benefits of language coaching to the teacher/learner dynamic.

Rethinking the Teacher-Learner Relationship

As teachers, we tend to feel as if we are underachieving if we do not put 120% effort into planning, designing, implementing, checking, testing, and discussing.

On the other hand, incorrectly calibrated and oftentimes needless work will just increase frustration and demotivate the learner. The issue here is the insistent focus on ourselves: our planning, our implementation, our checking.

But what about learner planning, learner implementation, and learner checking?

How about working just the amount needed to help learners reach their goals and allowing them to take ownership of their learning process?

By keeping in mind coaching guru Tony Robbins’ words, “Energy flows where attention goes,” you can learn to direct this flow to concentrate on what is truly necessary. This leads to less fretful preparation for the teacher and heightened learner autonomy.

Research Says…

The above coincides with research in the field of learning. In fact, a workplace learning report from LinkedIn suggests that:

Over 40% of Gen Z and millennial learners and 33% of Gen X and boomer learners prefer self-directed learning experiences, or opportunities to craft their own learning goals and choose the learning content that helps achieve them.1

Language coaching is intended to make time for understanding your learners’ language learning goals and how to best reach them. It’s about figuring out steps towards becoming a more effective learner and communicator.

As you engage in coaching-style activities and conversations, you will notice that learner engagement grows. Consequently, it will be easier for you to come up with motivating activities, as learners are already focused and ready to learn.

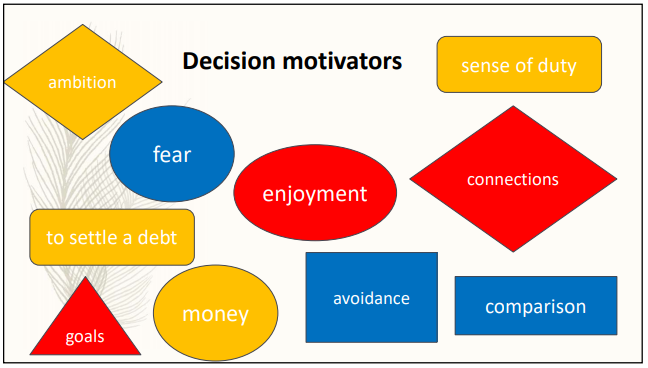

The Learning/Teaching Matrix

In order to find out more about learner autonomy in the classroom, take a look at this matrix.

If we rethink the roles that we as teachers have traditionally been assigned—or have assigned ourselves—we might start redesigning the basic components of our classes.

To highlight a few:

- Decision-making processes (top-down vs. collaborative)

- Classroom language (instruction vs. questions/statements)

- Processes (pre-planned vs. on the spot)

- Creativity (low vs. high)

- Correction work (controlled vs. open)

- Strategies to overcome challenges (few vs. many)

- Materials usage (excessive vs. moderate)

- Rewards and success focus (macro vs. micro)

Colour Zones in Teaching

With a coaching mindset, your lessons will mostly tend to be in the green, occasionally yellow and blue zones. More traditional approaches to teaching will primarily be in the red zone, with occasional excursions into the yellow and blue zones.

The ‘greener’ your teaching becomes, the more it will lead to:

- Collaboration in partnership settings

- Diverse thinking

- Multiple pathways to reach goals

- Exploration of a wider set of skills and competencies

- Stronger awareness of learning strategies

- Promotion of learner strengths and successes

- Clearly defined goals and clear communication

Small Tweaks, Big Gains

What we have found out so far points towards learner empowerment, increasing flexibility, and resilience—and we must surely agree that in these turbulent times we can all do with a larger dose of these.

Coaching can help here because it is largely based on asking the right questions.

This leads to opening up conversations instead of instructing—paying attention with curiosity rather than with the intention to lead. In turn, learner autonomy will develop and flourish, breeding teacher and learner wellbeing that’s built on a high level of trust.

Focusing on micro-skills and rewarding on a small scale will create a safe learning environment.

However, if we fail to support learners when facing their weaknesses and blocks, these will persist and resurface as low motivation, boredom, and poor language learning skills. Working towards large-scale goals and celebrating only major successes will keep learners with lower self-esteem caught up in negative self-talk and believing they are not good enough.

Focusing on subskills and micro-skills and rewarding them on a small scale will create a safe learning environment. As they say, it’s about “progress, not perfection.” These small tweaks to teaching can all increase self-esteem for learners, which in turn leads to the motivation to make progress and learn more.

5 Practical Steps to Increase Learner Autonomy

Now that we know more about learner autonomy in theory, how can teachers and educators create a learning environment that enhances learner autonomy?

1. Use the 80/20 Rule

80% teacher silence enables 80% learner talking/thinking time. 20% teacher talking time is sufficient, no matter the language level.

Activity: Record yourself during a lesson and roughly add up your talking time. Do one thing differently to increase your learners’ active class participation time.

Reflection: What did you change? What changed?

2. Welcome Silence

Appreciate silence in class as thinking time not to be reduced in favour of “doing things.” Thinking is when your learners are creating connections, bridging earlier and new ideas, knowledge, and skills. The most valuable time in coaching is when the client is discovering, exploring, and figuring out how to proceed.

Activity: Count to 10 before you ask your next question, give your next instruction. Also, count to 10 after asking/instructing.

Reflection: How did things change? What reactions ensued?

3. Offer Guidance where Needed

Make sure you guide the reflective process at the ends of activities, lessons, courses with 2-3 very simple questions/activities.

Activity: Use a multi-sensory approach:

- How did this feel?

- What did you notice?

- What new thoughts do you have now?

- How does this sound to you?

(Naturally do not ask all at once, but choose the appropriate question after an activity, at the end of the lesson or a complete course.)

Reflection: Did their answers surprise you? How did these questions and the answers make you see, feel, and think about your class?

4. Flip the Classroom

Learners will be more motivated and feel more involved if, instead of telling them what to do (strongly instructing), you open up space and ask them which of 2-3 things they would like to move forward with during the lesson.

By giving choices, you build responsibility. As they begin to own the decision-making process, they will become more aware of the reasons underlying the choices they make.

By giving choices, you build responsibility.

Activity: Divide your learners into two groups. While Group 1 writes down the questions that they would ask as a teacher from the class before an exercise (e.g. “p. 42/ex. 4”), Group 2 writes down the instructions that they would give to the class as a teacher before that exercise.

Reflection: How do the different types of messages make the learners react and why? Which do they appreciate more and why?

5. Focus on Resources

Focus on the skill sets and techniques learners use when learning. Call attention to and ask about these strategies. This way learners become more aware and autonomous, and you can encourage them to be open to new learning-related ideas from each other.

Activity: Create a strengths/positivity wall. Ask learners to write down what they see as a learning-related strength or positive learning habit in the person sitting next to them. Put these on the wall (or whiteboard in Zoom).

Reflection: What one word describes this activity for you? And for your learners?

Adopt a Coaching Approach in Your Classes!

Have these ideas sparked your interest in more activities of this sort? Do you wish to unlock your learners’ potential? Gain clarity and structure to support a language coaching approach in your classes and trainings.

If you think this could be the missing piece in your language teaching puzzle – take the first step and visit our website.

https://internationallanguagecoaching.com/training-courses

Courses start each season, from foundation to advanced levels. Also, check out our ILCA YouTube* channel for insights.

*ILCA is the International Language Coaching Association.

References

1. https://learning.linkedin.com/resources/workplace-learning-report

↩